‘Do what you want’ Marieme’s new friends tell her, but how much choice is there for working class black girls from run-down estates on the margins of Paris?

In the spectacular opening scene of Girlhood, the girls look tough enough to break down any barriers life may put up. An all-female American football game is taking place under flood lights and the girls are bulked up in their kit, strong, unself-consciousness and physical, the image of girlpower. They walk home noisy and boisterous, but as they approach the estates where they live and one by one they split off there’s a palpable change of mood. They grow silent and uneasy, and struggle to hold their nerve as they walk the gauntlet of gangs of boys jeering and teasing. Inside their homes it’s their job to look after their younger siblings and the job of the men to watch over them. There’s an unnerving scene where Marieme (newcomer Karidja Touré) warns her young sister to hide the evidence of her puberty from their abusive brother. Marieme has already faced his threats and violence as he protects his own macho sense of honour by enforcing strict controls over her relationships with boys.

But Marieme is more interested in her new-found group of girlfriends. The film’s writer-director Céline Sciamma brilliantly captures that brief time when teenagers are yet to experience the reality of what their future might hold for them. When the gang of four bounce down the streets of Paris, it’s more Sleepover Club than Sex in the City. These girls aren’t dressing up for the boys, but to play out their fantasies. They may be shoplifting and stealing money and hiring hotel rooms, but it’s so they can eat pizza, sleep over and have fun together. Their friendships are intense, they’re funny, exuberant and optimistic, and no scene demonstrates this better than when they dance in stolen dresses to the entire of Rihanna’s ‘Diamonds’.

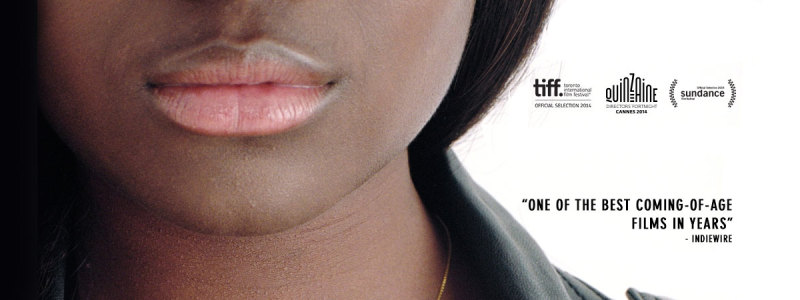

It’s a bittersweet moment. Excluded from high school, for Marieme the future looks mapped out like those around her, a job with low pay and long hours like her mother, or pregnancy, prostitution and drugs. The fact that the writer-director Céline Sciamma had to use non-actors scouted from the streets of Paris because, she says, agents don’t have many black girls on their books, and that this is the first French film to focus on the experience of black girls, reinforces a sense of wasted potential.

As the film tells the story of how Marieme navigates these constraints, it doesn’t pass judgement or spell out any political message. It avoids sentimentality, patronisation and cliché and instead it’s driven by characters and friendships that feel authentic, true and empowering.